Fall, 2023: we studied King Lear, Merchant of Venice, and Measure for Measure while observing Newton County court cases, visiting a state prison to discuss Shakespeare with incarcerated students, volunteering for a 5K that benefitted children with incarcerated parents, building a prison library from a UGA professor’s donations, and learning from guest lectures by Sammie Byron, Spencer Shelton, Clint Rucker, and Steve Nowicki.

“A testament to the dynamic, communal nature of education—one that thrives on shared passions, diverse perspectives, and the willingness to challenge and reform our understanding of the world” —Sabrina

Student Reflections

Ellie: It was difficult to write this reflection because I don’t quite want to be reflecting on this course yet. Three plays, fifteen weeks of class discussions, two essays, nineteen experiential hours, and one research paper, and, now, we are finished. It feels as though I could never be finished. Articulating this course’s impact on me is also difficult, because after a semester of learning, it is hard to imagine how my mind worked before as compared to my present after. But I suppose that not remembering what the before felt like is a good indication that I have thoroughly changed several understandings that I previously held. I think about spending time with the men at Burruss Correctional nearly every day — I wonder about how their days are different from my own, what they might be learning in their classes, and why I continue to linger on their lives as compared to mine.

Ellie & Sammie Byron

As part of the experiential component of Shakespeare & Law, I travelled to the Newton County Courthouse and watched petitioners in court shoulder through the process of plea bargaining, and then showed up in Criminal Justice to learn about it. I now paint the faces of Cordelia, Lear, Shylock, Portia, Antonio, Isabella, Angelo, and the Duke in my mind as people I see in my day-to-day life.

Shakespeare & Law has forced me to confront the fact that Shakespeare can be found, like it or not, everywhere, all the time. This has been a good and bad realization for me. I am haunted by Angelo’s taunts toward Isabella, but I am also glad to have met these characters. Isabella and I share a name, and perhaps that is why her story has carved out a home within my heart, but I think it is more than that. Something instinctual clawed at my conscience hearing “Who will believe thee, Isabel?” that I have rarely felt from any kind of literature. Sitting in courtrooms and seeing Lear in the face of an older party in a civil suit, or picturing Shylock’s trial in criminal court were experiences I never would have had without this course. While it hurts me to see Shakespearean tragedy, and even worse, comedy, in our criminal justice system, I am glad that I will never unsee it. It needs to be seen. That is more clear to me than ever.

While it hurts me to see Shakespearean tragedy, and even worse, comedy, in our criminal justice system, I am glad that I will never unsee it. It needs to be seen. That is more clear to me than ever

Ellie

People can change, as Sammie Byron shared in his talk with Oxford students in November. I also took that message to heart. Being vulnerable while acting out Hamlet with the men at Burruss, being vulnerable while sharing thoughts about Shakespeare in class, and being vulnerable by submitting my research paper to the National Conference: these are all actions that require both myself and others to try to understand each other. This Shakespeare class has reminded me what I love so much about learning, especially literature courses. To learn is to make oneself vulnerable to other points of view, criticism, and new ideas. And I feel as though I have absolutely addressed that fact this semester, as I feel all my peers did as well. While this may not have answered the prompt(s) in full, I think it fairly represents my own value of Shakespeare, literature, and this course. I will continue to be vulnerable, as I was at Burruss, and to see Shakespeare all around me, not because this experience has changed me in my entirety, but because it has reminded me of the value of doing so. –Ellie

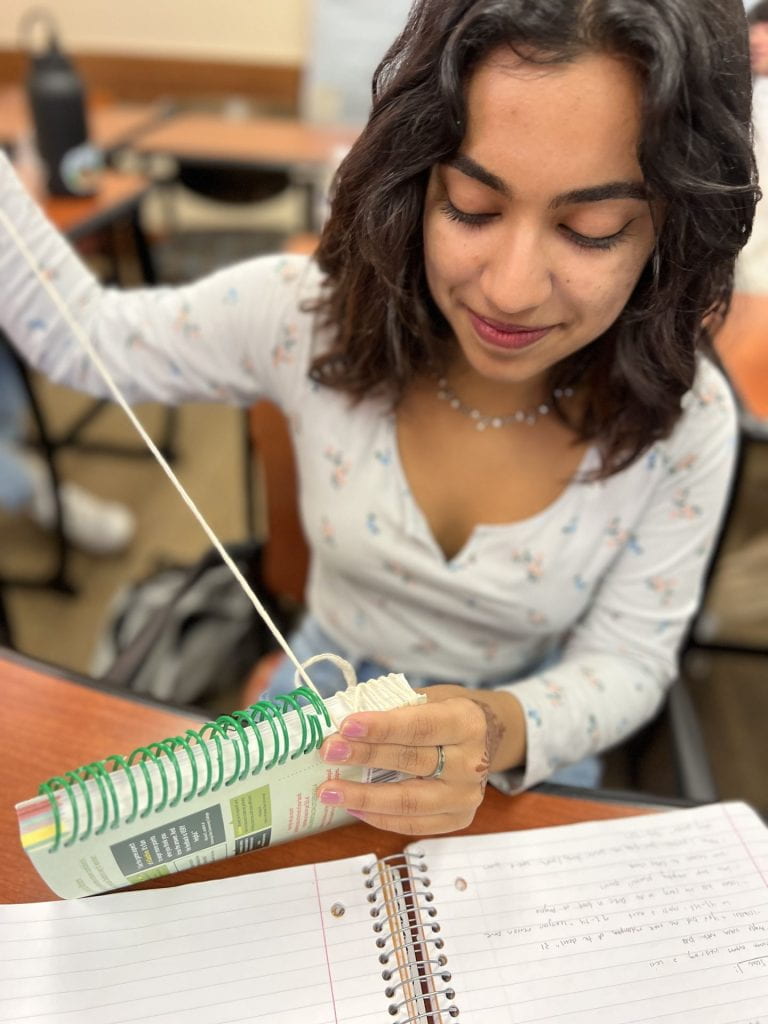

Shannan converts book bindings for the prison classroom

Shannan: I had never considered awe before taking this course. But in both of my visits to Burruss Correctional, I was invited to contemplate awe in a way that I never had before that will continue to inform the way that I view life for years to come.

I didn’t know what to expect going into my first visit to Burruss, but within the first ten

minutes in the classroom, I felt welcome in a way that I have rarely experienced. The first thing we did was introduce ourselves to each other, which is not something that I have frequently experienced in academic environments. Having the time to get to know the host students on an individual level before class even started was incredibly valuable, as it gave us a basis of connection that I think helped us all be a little more vulnerable.

We then dove into the discussion of awe. This subject was fascinating to me because we live in a society that emphasizes productivity over reflection, and the resulting push to always be doing more can blind us to the daily moments that make life beautiful. The discussion helped forge a bond within the class: no two people had the same “awe” experiences, but we could all understand our shared emotions behind them. It was a strong reminder of our shared humanity in a world that can feel impossibly divided.

In my second visit to Burruss, I had the privilege of bringing Oxapella to perform for the host students as well as hearing Ryan perform. The experience was a study in awe in and of itself. I Ioved hearing Ryan’s interpretation of Fly to Paradise, especially with his addition of the viola. It was incredible. It represented that one valuable thing that I have learned throughout this course is dignity in the face of the law. The United States prison and legal systems are brutal and broken, and yet there are people every day working to improve it. There are incarcerated people learning Shakespeare. There is hope. I think it’s really beautiful that even in the face of such a cruel and unjust system, it is possible to find humanity and respect for other people, sometimes in an even greater capacity than we find in society today. I found my experiences within Burruss Correctional to be humbling and informative on the realities of life within the prison system. It was an honor to be able to visit. –Shannan

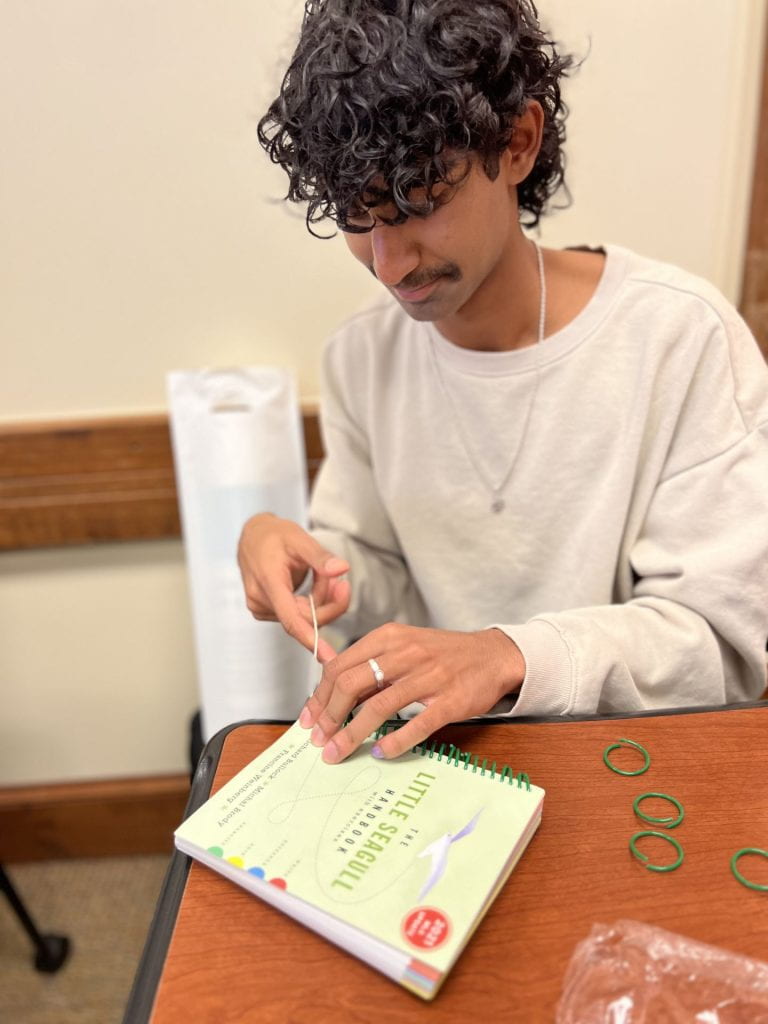

Dylan modifying books for prison compliance

Dylan: My visit to Burruss Correctional Training Center greatly aided in my understanding of the three Shakespeare plays we read this semester through gaining an understanding of how individuals can be treated by a system of law. Also, through understanding the distinct perspectives of individuals who are incarcerated. My apprehensions before our visit to Burruss Correctional Training Center were fueled mainly by a lack of understanding. The media paints a negative and defamatory image of people who are incarcerated; this was my only reference point before our visit. But as soon as those of us from Emory stepped in the classroom, we were greeted by warm, kind men who were cracking jokes with one another and genuinely excited to learn Shakespeare alongside us. I shook hands with each of the men and we shared introductions.

Any apprehensions I’d had before entering the classroom immediately dissipated. It was wonderful to put on a quick production of act 1 of Hamlet. We were each given the opportunity to use our specific skills and gifts to bring each character and rendition to life. This was evident in the three different interpretations of the scene; each production was engaging and fulfilling to observe. Acting itself is special in the sense that who you were before you became your character ceases to matter, no matter how experienced you are with acting. The distinction between host and traveling students became obsolete. Similar to Shylock, the men who are incarcerated are treated and viewed as other due to their predicament; paralleling Shylock, again, these views are rooted solely in prejudice, defamatory media representations, and a lack of understanding/education. My visit to Burruss Correctional Training Center has allowed me the opportunity to educate myself and disregard hurtful and incorrect stereotypes regarding individuals who are incarcerated. I’m incredibly grateful that I had the opportunity to learn Shakespeare alongside the men at Burruss. This was an unforgettable experience and I hope I’ll have the opportunity to learn alongside students who are incarcerated again. –Dylan

Jon: Recently, I attended a town hall meeting held by a city council member near my hometown looking to get reelected. During the question and answer segment of his talk, the speaker used the phrase “those guys need to be put behind bars” regarding a question of gun violence that was brought up. Prior to this class I never would have thought much of this phrase but I found myself really exploring what this phrase truly meant. It reminded me of Shylock’s unyielding demand for justice, regardless of the moral implications.

Jon & others outside Burruss

My visit to the prison this semester was especially eye-opening, revealing the human cost of our justice system. As I walked through the corridors, I couldn’t help but draw parallels to Shylock’s plight. I pondered the distinction between those who ‘deserve’ their sentence and those who might be victims of a system more concerned with punishment than rehabilitation. This experience made me question the true nature of justice – is it merely punitive, or does it have a role in reforming and rehabilitating? –Jonathan

The fusion of classroom learning with beyond-the-classroom experiences in this course has provided a multifaceted understanding of justice as depicted in literature and as experienced in real life. The plays of Shakespeare, with their timeless exploration of law, justice, and human nature, along with the practical insights from prison visits and court observations have deepened the understanding of the complexities of the criminal justice system. They demonstrate that while the context and presentation of justice might evolve over time, the fundamental questions about fairness, mercy, and morality remain perennially relevant. This course has not only enhanced literary appreciation but also fostered a more nuanced and empathetic understanding of the real-world implications of justice and the law. –Kaity

Kaity & Sophie getting coffee after the courtroom

Sabrina: The first-hand experience of walking into a prison classroom revealed an unexpected environment—one that transcended all my expectations. The welcoming atmosphere, akin to a community gathering, erased the boundaries between the host and traveling students. The pre-class conversations mirrored the lively exchanges before a typical classroom session, highlighting the shared passion for learning that unified us. This setting became a microcosm of the diverse yet interconnected nature of the justice system—a place where camaraderie prevailed despite societal divides.

Engaging with host students further underscored the universality of the passion for learning. What initially seemed like a formal engagement focused on coursework evolved into a platform for building personal connections and broadening my understanding of the world. These interactions became integral to my learning, emphasizing that education extends beyond textbooks and assignments. The vibrancy of shared experiences and connections became a catalyst for personal growth, enriching my understanding of justice, morality, and the human experience. The realization that, regardless of our roles as hosts or traveling students (incarcerated or free people), we were all part of a collective pursuit of knowledge underscores the transformative power of education in fostering unity and understanding.

The integration of firsthand experiences into our exploration of Shakespeare has not only deepened my understanding of criminal justice but has also instilled a commitment to continuous learning and transformation. The prison visit and the connections forged therein serve as a testament to the dynamic, communal nature of education—one that thrives on shared passions, diverse perspectives, and the willingness to challenge and reform our understanding of the world.

This semester prompted the development of an odd yet compelling metaphor in my thinking about the justice system and law. Reflecting on my experiences, from initially closed-mindedness to a reformed perspective, raised questions about why the justice system can’t operate similarly—why its actions aren’t comparable to those of a person. The prison visit taught me the importance of being open to learning from anyone and breaking free from the belief that knowledge can only be acquired in a formal classroom setting.

The integration of firsthand experiences into our exploration of Shakespeare has not only deepened my understanding of criminal justice but has also instilled a commitment to continuous learning and transformation.

—Sabrina

Observing court proceedings shattered my preconceived notions about the fairness of the system. After seeing every single person in a row take the plea deal and plead guilty, following the suggestion given by the public defender who was taking on a multitude of cases just in an hour, it opened my eyes to how the system sets certain people up to fail. The realization that individuals, often with limited resources, were urged to take plea deals without a fair chance at trial exposed systemic flaws. The plays we read in class, along with external readings, provided a lens to analyze these injustices within a Shakespearean context, making it easier to discern parallels with contemporary systems.

I even had preconceived notions about Shakespeare’s plays as I did not see any benefit to reading them in high school. But now I am able to see how Shakespeare’s plays helped me learn many important themes within what we were learning outside of class. This transformation in thinking led me to question the justice system as if it were a person—a thought experiment that contemplated whether a system that has lived through numerous atrocities could reform itself. The desire to see the justice system put on trial emerged from a belief that, just like an individual, it should be subject to scrutiny and accountability. —Sabrina

Elena: The intersection of Shakespeare’s plays and law is one I had not considered before taking English 311. As the class progressed, however, studying property laws and the idea of material ownership led me to question who truly “owns” Shakespeare. Students of elite colleges, English professors, archival researchers, and prestigious conferences all lay metaphorical claim to the study and interpretation of his work, but it is easy to forget that Shakespeare himself would have been a stranger in these places. Still, we see the very idea of “Shakespeare” become deeply material and, subconsciously, inextricably intertwined with immense wealth and privilege. The silent, shrinelike grounds of the Folger Shakespeare Library, treasured “possession” of First Folios, and extraordinarily expensive performances in the opulent theaters of London’s West End all compete to evidence true appreciation of the greatest literary works of English.

But it is precisely this phenomenon of Shakespeare-as-object that makes the prison performances we experienced as a class truly disruptive. In an environment completely devoid of the objects we associate with Shakespeare, few resources—including freedom itself—reveals how Shakespeare fosters healing and renewal come from the most unlikely of places.

The harsh environment of prison is a call to humility not just for those incarcerated, but also for us. In these spaces, it is not about us: the people trusted with the privilege to come and go. We minimize our footprint, follow the rules, and pass through as quietly as possible, anxious to not to cause any trouble. Still, we experience the sense of wonder that comes with seeing firsthand how incredible talent makes the best of nearly unbearable conditions, reintroducing the powerful sense of humanity that gives Shakespeare’s plays their magnetic appeal.

Elena unloading books for the prison library

Although I was able to visit Burruss Correctional Training Center, a Georgia state prison, only once this semester, Dr. Higinbotham’s extensive experience working in the prison system with her nonprofit, Common Good Atlanta, has hugely impacted the way I read Shakespeare. The experiential portion of this class as a whole has been incredibly enlightening, and I was able to take advantage of a variety of opportunities to ground Shakespeare in the real world. The presentation Dr. Steve Nowicki gave on the locus of control helped inspire my essay on King Lear, where I discussed different conceptions of fate borrowed from ancient myth and connected the different ways Lear ’s characters responded to difficult situations. I believe Dr. Nowicki would agree that the incarcerated students who take advantage of opportunities like the classes offered by Common Good Atlanta demonstrate a strong internal locus of control by taking steps to continue their own personal development. I also had the opportunity to peer review a paper on the violence of the law as connected to the public school system by Ryan, an incarcerated student at Burruss, then met and spoke with him during our class visit. Although I did not agree with much of what he wrote, I was able to inhabit the other side (as Shakespeare so often calls on us to do!) and offer some helpful suggestions to strengthen his argument. The humility and awe inspired by these interactions is a small reminder that we are all just passing through, and the idea of performance as ownership, and of reclaiming ownership of self through art, has madeShakespeare’s texts more approachable and much more real to me. –Elena

Virat & peers with Dr. Paul Roman

The allowance of free thought and analysis in Shakespeare and Law truly allowed me to grasp the injustices in our system. In my Merchant of Venice essay, I was able to let my thoughts take the reins of my writing. The more I wrote, the more infuriated I became with just how many connections could be drawn between the American justice system and what I would have thought to be a seemingly ‘outdated’ play. The essay was easier to complete than it should have been. I realized that the injustices of the Merchant of Venice sadly live on strongly in American society. I was confused why I felt so much more strongly about the justice system after reading a play from the sixteenth-century and writing an essay when I have grown up with these atrocities happening all around me. I know that I am privileged and do not have to endure the same injustices as others do–but how is Shakespeare of everything the thing that wakes me up? The answer is perspective. Reading a play from the sixteenth century allowed me to conceptualize how our society compares against a 400-year-old, fictional reality (a little too similar). We dump minorities into prison at unprecedented disproportionate rates, placing them out of our sight and out of our minds. Just like Venetian society locked away Jewish people behind the gates of the ghetto to “protect” Christians. We utilize the disguise of the law and its incomprehensible intricacies to hurt marginalized communities, furthering unacceptable social and political intentions. Similarly, Shylock’s lack of legal knowledge, coupled with cultural affiliation, depreciates his given contractual rights, taking away his right to receive what he is due according to the very letter of the law. Taking my Merchant of Venice essay and expanding it into my final research paper solidified my newly formed feelings about American law. —Virat