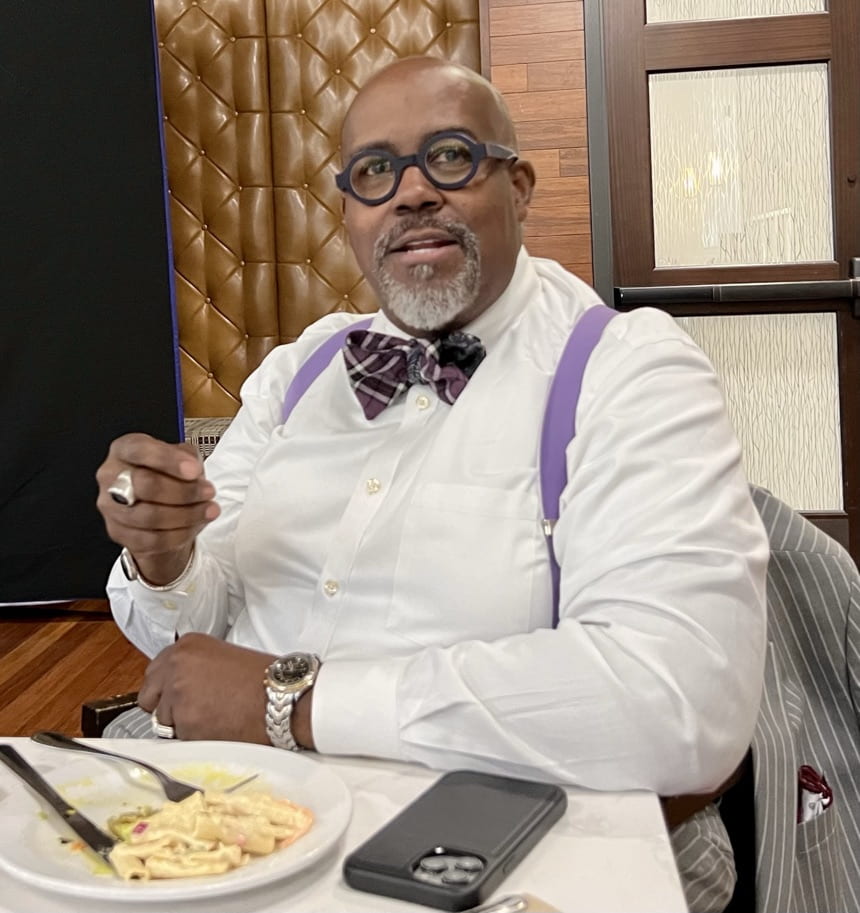

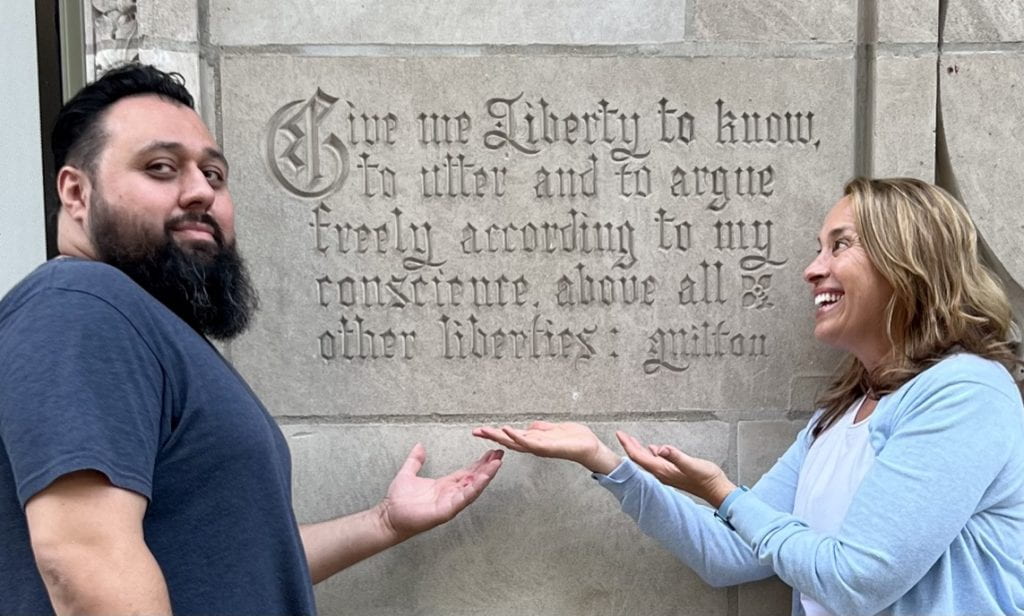

I’m excited to welcome my friend, Dr. Ellen Stockstill, to discuss her fabulous book, Faking It: Victorian Documentary Novels. Come and gain new insight into novels by Charles Dickens, the Brontës, Mary Shelley, and others—with a Victorian literature scholar and inspiring human being.